In industrial production of chocolate and high-fat confectionery, there is a misunderstanding regarding the role of cooling systems. The prevalent industry approach is to treat a cooling tunnel as a “refrigerator on a belt.” This is a fundamental error. A cooling tunnel is not a storage unit; it is a high-speed thermodynamic heat exchanger. When the logic of this exchange—specifically the Cooling Delta—is ignored, the result is a massive, often invisible, “Ignorance Tax” paid in energy waste, product rejection, and lost shelf life.

After 15 years of observing facilities ranging from small-scale artisanal labs to 100,000 sq. ft. industrial complexes, we can say this with certainty: the most profitable Chocolate factory are not those with the newest machines, but those with the tightest Process Flow Logic. In the following deep dive, we examine why micron level precision in thermal synchronization is the only sustainable path to international quality standards.

The Micron Mindset: Beyond Temperature Set-Points

As a standard factory protocol, an operator looks at a PLC screen, sees a set-point of 14°C, and assumes the process is under control. However, from an industrial perspective, a single temperature reading is a “vanity metric.” To achieve a world-class finish, we must look deeper into the molecular behavior of the product itself.

Chocolate is a complex matrix of cocoa butter crystals. These crystals are polymorphic, meaning they can exist in multiple forms, most of which are unstable(Read our blog Understanding Fats in Your Chocolate Part 2 to know more about Polymorphism). The goal of the cooling process is to preserve the Form V (Beta) crystals created during tempering. This preservation is entirely dependent on the Cooling Delta—the differential between the product’s core temperature and the temperature of the cooling medium.

If this delta is too wide, the product undergoes “Thermal Shock.” The outer shell hardens too rapidly, trapping latent heat inside. This heat eventually migrates to the surface, bringing fats with it and causing “Fat Bloom.” Conversely, if the delta is too narrow, the crystallization process is incomplete, resulting in a soft, dull product that sticks to packaging. Precision engineering requires a delta that evolves across the length of the tunnel, synchronized to the specific fat profile of the recipe.

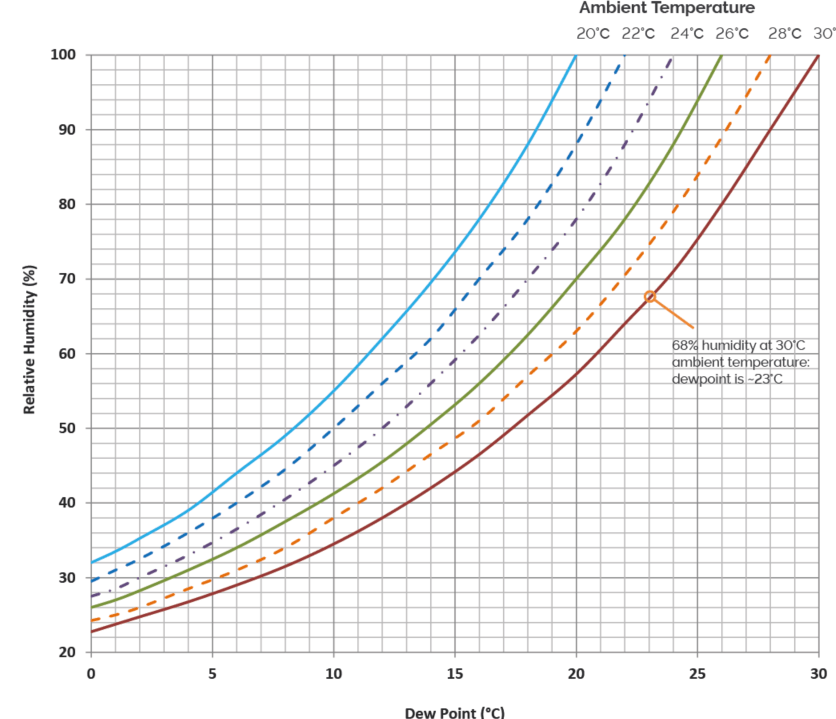

The Dew Point Trap: The Invisible Variable in Utility Logic

One of the most frequent causes of financial loss in chocolate/confectionery production is a variable that many engineers fail to track: The Dew Point. (Read more about Dew Point and Blooms in our Blog Blooming in chocolates).A cooling tunnel does not operate in a vacuum; it is constantly interacting with the ambient air of the facility.

Image Credit:- Oxford Instruments

When a cooling tunnel is operated without regards for psychrometric(hygrometric, thermal, or humidity-related) logic, it becomes a “Condensation Magnet.” If the cooling air inside the tunnel drops below the dew point of the factory floor, a microscopic layer of moisture forms on the product surface at the exit. This moisture dissolves the surface sugar. As the product moves into storage, the moisture evaporates, leaving behind white sugar crystals. This is Sugar Bloom, and it is almost always misdiagnosed as a “bad chocolate batch” when it is, in fact, a “bad logic.”

At the audit level, we solve this by calculating the “Vapor Pressure Gap.” The exit zone of a tunnel must be commissioned in such a way, so as to slightly raise the surface temperature of the product to just above the ambient dew point of the packaging room. Without this micron level calibration of the environment, even the most expensive European machinery will produce sub-standard results.

The Scaling Gap: Why “More” Usually Means “Worse”

A critical transition occurs for chocolate companies in the 2-to-5-year growth phase. As these companies scale from batch processing to continuous industrial lines, they often encounter a “Quality Wall.” What worked for a 50kg batch—where cooling was slow and ambient—fails catastrophically when applied to a continuous belt moving at 3 meters per minute.

This is the Scaling Gap. In an industrial line, the product is in the tunnel for a limited window of time (the “Residence Time”). To achieve the same crystallization in 8 minutes that used to take 2 hours in a fridge, the thermodynamic flow must be redesigned.

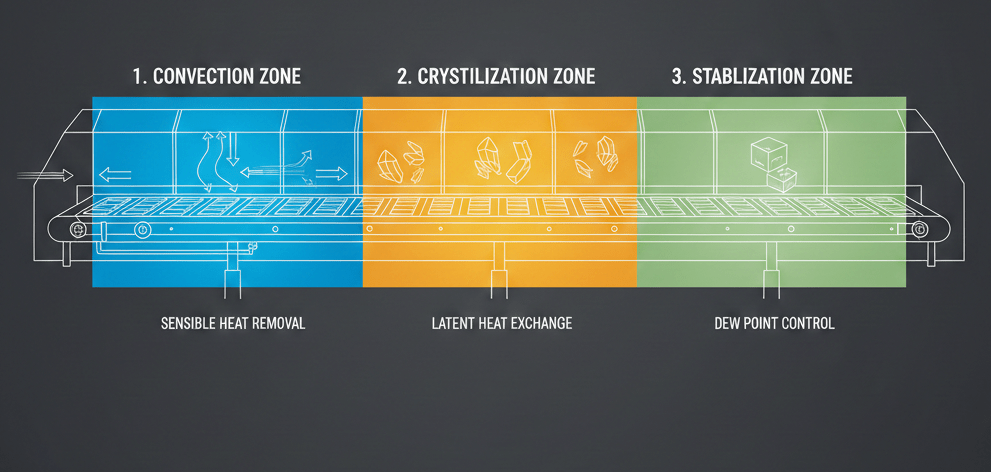

An industrial cooling tunnel must be viewed as a three-stage system:

- The Convection Zone: Removing the initial “sensible heat” from the enrobing or molding process.

- The Crystallization Zone: The most sensitive stage, where airflow velocity must be precisely tuned to remove the “latent heat” of the fat without causing a surface-to-core temperature mismatch.

- The Stabilization Zone: Preparing the product for the “Real World” (the packaging room) by stabilizing the surface against humidity.

When a facility attempts to scale without re-architecting these three zones, they pay the Ignorance Tax in the form of “Bloom Claims” from retailers—a cost that can easily reach thousands of dollars/lakhs of rupees in a single season.

The Caramel Paradox: Thermodynamics of Multi-Layer Systems

For manufacturers of caramel-filled or enrobed products, the Cooling Delta presents a unique paradox. Caramel and chocolate have vastly different Thermal Conductivities. Caramel holds onto heat like a capacitor, while chocolate sheds it quickly.

When these two substances meet, they enter a thermodynamic battle. If the caramel center is not pre-conditioned to a specific “Internal Logic,” it will continue to release heat long after the chocolate has set. This internal heat-soak ruins the temper of the chocolate from the inside out, leading to a product that looks perfect at the tunnel exit but turns grey and soft in the warehouse 48 hours later.

Solving the Caramel Paradox requires a “Utility Sync.” The infrastructure—chilled water, air handling, and belt speed—must be tuned to accommodate the specific cooling curve of the caramel center. This is not a “maintenance” task; it is Logic Audit.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond Commodity Engineering

The chocolate industry is currently divided into two types of operators: those who view engineering as a “Hardware Expense” and those who view it as a “Logic Asset.”

The “Hardware” approach leads to a cycle of constant firefighting—tweaking temperatures, adding fans, and hoping for a better batch tomorrow.(How many times you know a Chocolatier who has reached out to you and said that he is adding another fan to the conveyor belt, or adding a Dehumidifier in the modelling room).

The “Logic” approach, which we champion at Rudvik Engineers, treats the entire facility as a single, synchronized engine, which is the “Most Profitable way”.

The thousands of dollar mishaps often seen in struggling facilities is rarely due to a lack of sales; it is due to a lack of Efficiency Logic. Every 1% reduction in scrap, every 5% reduction in energy waste from over-chilling, and every 10% increase in line speed through better thermal synchronization goes directly to the bottom line.

As raw material costs rise and global competition increases, the “Ignorance Tax” is no longer a cost of doing business—it is a threat to the business’s existence. Precision is no longer a luxury for the elite; it is the baseline for survival.

Technical Brief: The “Audit-First” Checklist

For plant managers and owners seeking to escape the cycle of approximations, the following three checks should be conducted immediately:

- Airflow Velocity Mapping: Is your tunnel cooling evenly across the belt width, or is the center cooling faster than the edges?

- Dew Point Synchronization: Is your tunnel exit temperature at least 2°C above the dew point of your packaging room?

- Latent Heat Calculation: Does your cooling curve account for the specific fat percentage of your 2026 recipes?

If these questions cannot be answered with micron level data, the system is operating on “approximations.” And in the world of high-value process engineering, an approximation is simply an unplanned expense.

Book an Industrial Discovery Session today to talk to us for your cooling delta problems.

Explore how we design multimillion dollar factories.

The cocoa Blueprint